Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Performers and composers

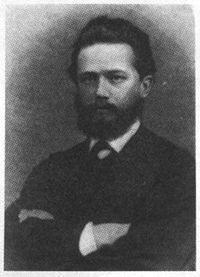

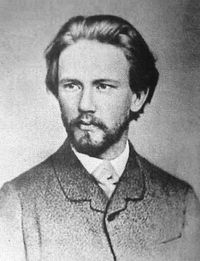

Pyotr (Peter) Ilyich Tchaikovsky (Russian: Пётр Ильич Чайкoвский, Pëtr Il’ič Čajkovskij; listen ) ( 7 May [ O.S. 25 April] 1840 – 6 November [ O.S. 25 October] 1893), was a Russian composer of the Romantic era.

Although not a member of the group of Russian composers usually known in English-speaking countries as ' The Five', his music has come to be known and loved for its distinctly Russian character as well as for its rich harmonies and stirring melodies. His works, however, were much more western than those of his Russian contemporaries as he effectively used international elements in addition to national folk melodies.

Early life

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky was born on May 7, 1840 (by the Gregorian calendar; this was April 25 by the Julian calendar) in Votkinsk, a small town in present-day Udmurtia (at the time the Vyatka Guberniya under Imperial Russia). He was the son of Ilya Petrovich Tchaikovsky, a mining engineer in the government mines, and the second of his three wives, Alexandra Andreyevna Assier, a Russian woman of French ancestry. He was the older brother (by some ten years) of the dramatist, librettist, and translator Modest Ilyich Tchaikovsky.

Pyotr began piano lessons at the age of five, and in a few months he was already proficient at Friedrich Kalkbrenner's composition Le Fou. In 1850, his father was appointed director of the St Petersburg Technological Institute. There, the young Tchaikovsky obtained an excellent general education at the School of Jurisprudence, and furthered his instruction on the piano with the director of the music library.

Also during this time, he made the acquaintance of the Italian master Luigi Piccioli, who influenced the young man away from German music, and encouraged the love of Rossini, Bellini, and Donizetti. His father indulged Tchaikovsky's interest in music by funding studies with Rudolph Kündinger, a well-known piano teacher from Nuremberg. Under Kündinger, Tchaikovsky's aversion to German music was overcome, and a lifelong affinity with the music of Mozart was seeded. When his mother died of cholera in 1854, the 14-year-old composed a waltz in her memory.

Tchaikovsky left school in 1858 and received employment as an under-secretary in the Ministry of Justice, where he soon joined the Ministry's choral group. In 1861, he befriended a fellow civil servant who had studied with Nikolai Zaremba, who urged him to resign his position and pursue his studies further. Not ready to give up employment, Tchaikovsky agreed to begin lessons in musical theory with Zaremba.

The following year, when Zaremba joined the faculty of the new St Petersburg Conservatory, Tchaikovsky followed his teacher and enrolled, but still did not give up his post at the ministry, until his father consented to support him. From 1862 to 1865, Tchaikovsky studied harmony, counterpoint and the fugue with Zaremba, and instrumentation and composition under the director and founder of the Conservatory, Anton Rubinstein, who was both impressed by and envious of Tchaikovsky's talent.

Musical career

After graduating, Tchaikovsky was approached by Anton Rubinstein's younger brother Nikolai to become professor of harmony, composition, and the history of music. Tchaikovsky gladly accepted the position, as his father had retired and lost his property. The next ten years were spent teaching and composing. Teaching was taxing, and in 1877 he suffered a breakdown. After a year off, he attempted to return to teaching, but retired his post soon after. He spent some time in Switzerland, but eventually took residence with his sister, who had an estate just outside Kiev.

Tchaikovsky took to orchestral conducting after filling in at a performance in Moscow of his opera The Enchantress (Russian: Чародейка) (1885-7). Overcoming a life-long stage fright, his confidence gradually increased to the extent that he regularly took to conducting his pieces.

Tchaikovsky toured the United States in 1891 conducting performances of his works. On May 5, he conducted the New York Music Society's orchestra in a performance of Marche Solennelle on the opening night of Carnegie Hall. There were performances of his Third Suite on May 7, and the a cappella choruses Pater Noster and Legend on May 8. The U.S. tour also included performances of his First Piano Concerto and Serenade for Strings.

Just nine days after the first performance of his Sixth Symphony, Pathétique, in 1893, in St Petersburg, Tchaikovsky died (see section below). Some musicologists (e.g., Milton Cross, David Ewen) believe that he consciously wrote his Sixth Symphony as his own Requiem. In the development section of the first movement, the rapidly progressing evolution of the transformed first theme suddenly "shifts into neutral" in the strings, and a rather quiet, harmonized chorale emerges in the trombones. The trombone theme bears no relation to the music that either preceded or followed it. It appears to be a musical "non sequitur" — but it is from the Russian Orthodox Mass for the Dead, in which it is sung to the words: "And may his soul rest with the souls of all the saints."

His music included some of the most renowned pieces of the romantic period. Many of his works were inspired by events in his life.

Personal life

Tchaikovsky's homosexuality, as well as its importance to his life and music, has long been recognized, though any proof of it was suppressed during the Soviet era. Although some historians continue to view him as heterosexual, others — such as Rictor Norton and Alexander Poznansky — conclude that some of Tchaikovsky's closest relationships were homosexual (citing his servant Aleksei Sofronov and his nephew, Vladimir "Bob" Davydov). Evidence that Tchaikovsky was homosexual is drawn from his letters and diaries, as well as the letters of his brother, Modest, who was also homosexual.

One of Tchaikovsky's conservatory students, Antonina Miliukova, began writing him passionate letters around the time that he had made up his mind to "marry whoever will have me." He did not even remember her from his classes, but her letters were very persistent. Tchaikovsky hastily married her on July 18, 1877.

Within days, while still on their honeymoon, Tchaikovsky deeply regretted his decision. By the time the couple returned to Moscow on July 26, he was a state of near-collapse. Two weeks after the wedding the composer supposedly attempted suicide by wading waist-high into the freezing Moscow River, certain he would contract a fatal case of pneumonia. His robust physical constitution defeated that plan, and his mental state grew even worse.

Tchaikovsky fled to St Petersburg, his mind verging on a nervous breakdown. Once there, after a violent outburst, Tchaikovsky lapsed into a two-day coma. A mental specialist recommended Tchaikovsky make no attempt to renew his marriage, nor try to see his wife again. The composer never returned to his wife but did send her a regular allowance through the years. They remained legally married until his death.

As Tchaikovsky biographer Anthony Holden points out, the debacle with Antonina forced Tchaikovsky to face the truth concerning his sexuality. For the rest of his life, he would never consider matrimony as a camoflauge or escape from his homosexuality. Neither woud he delude himself of being as capable of loving women as for men. He admitted, as he wrote to his brother Anatoly, there was "nothing more futile than wanting to be anything other than what I am by nature."

Far more influential than Antonina in Tchaikovsky's life was a wealthy widow, Nadezhda von Meck, with whom he exchanged over 1,200 letters between 1877 and 1890. At her insistence they never met; they did encounter each other on two occasions, purely by chance, but did not converse. As well as financial support in the amount of 6,000 rubles a year, she expressed interest in his musical career and admiration for his music. However, after 13 years she ended the relationship unexpectedly, claiming bankruptcy.

Tchaikovsky's death

Nine days after the premiere of the Sixth Symphony, Tchaikovsky died on 6 November 1893.

Most biographers of Tchaikovsky's life have considered his death to have been caused by cholera, most probably contracted through drinking contaminated water several days earlier. In recent decades, however, various theories have been advanced by some sources that his death was a suicide. According to one version of the theory, this represented a sentence imposed by a "court of honour" of Tchaikovsky's fellow-alumni of the St. Petersburg School of Jurisprudence, in censure of the composer's homosexuality.

In her never-published book Tchaikovsky Day by Day, the Russian musicologist Aleksandra Orlova argued for suicide based on oral evidence and various circumstantial events surrounding his death (such as discrepancies over death dates, and handling of Tchaikovsky's body), suggesting that Tchaikovsky poisoned himself with arsenic. Orlova cites no documentary reference for these claims, however, relying on oral commentary. Tchaikovsky biographer Anthony Holden goes into detail over the various trials Orlova and her husband suffered at the hands of Soviet censors, since the subjects of Tchaikovsky's death and his homosexuality were both considered forbiden for discussion officially.

Other well-respected studies of the composer have challenged Orlova's claims in detail, and concluded that the composer's death was due to natural causes. Holden mentions one other theory—that drinking unboiled water may not have been the only way Tchaikovsky could have contracted cholera. Referencing cholera specialist Dr. Valentin Pokovsky, Holden mentions the "faecal-oral route"—that Tchaikovsky could have possibly have contracted cholera from less than hygenic sexual practices with male prostitutes in St. Petersburg. This theory was advanced separately in The Times of London by its then-veteran medical specialist, Dr. Thomas Stuttaford.

Holden admits that while there is no further evidence to support this theory, if it had been true, Tchikovsky and Modest would have both gone to great pains to conceal the truth. By mutual agreement, they could have staged the drinking of the glass of unboiled water for the sake of family, friends, admirers and posterity. In the case of an almost sacred national figure, as Holden claims Tchaikovsky was by the end of his career, the doctors involved with Tchaikovsky's case might have permitted their medical consciences to go along with such a deception.

This mutual agreement with Modest and the doctors could have just as easily proved true regarding the "court of honour" theory, though Holden points out there is one final irony to that thesis. Had Tsar Alexander III received a letter of complaint about Tchaikovsky's indiscretions, he probably would have consigned it to the nearest waste-paper basket. Tchaikovsky was the Tsar's favorite composer, and the monarch was well aware of the homosexuality said to be rife amid his own courtiers and close relatives, some of those relatives ensconced in high public positions. As the Tsar is supposed to have said upon hearing upon the composer's death, "We have many dukes and barons, but only one Tchaikovsky."

Holden maintains, though, that this final point actually strengthens the theory that Tchaikovsky committed suicide, because it underlines what Holden calls "the fundamental assumption" that Tchaikovsky would have preferred death to public exposure of his sexual nature, whatever the consequences.

Without strong evidence for any of these cases, it is possible that no definite conclusion may be drawn and that the true nature of the composer's end may remain in dispute amongst researchers.

The English composer Michael Finnissy composed a short opera, Shameful Vice, about Tchaikovsky's last days and death.

The Funeral

When Alexander III received news of Tchaikovsky's death, he volunteered to pay the costs of the composer's funeral himself and directed the Directorate of the Imperial Theatres to organize the event. Poznansky observes this action shows the exceptional regard with which the Tsar regarded the composer. Only twice before had a Russian monarch shown such favour toward a fallen artistic or scholarly figure. Nicholas I had written a letter to the dying Alexander Pushkin following the poet's fatal duel. Nicholas also came personally to pay his final respects to historian Nikolay Karamzin on the eve of his burial.

The outpouring of grief over Tchaikovsky's death, and the resulting interest in his funeral, was extremely great. Tchaikovsky's funeral took place on 9 November, 1893 in Saint Petersburg. Participation in the funeral procession was by special ticket only. This ticket included entrance to Kazan Cathedral, where the funeral was to take place, and access to the cemetery of Alexander Nevsky Monastery. Kazan Cathedral holds 6,000 people. Sixty thousand people—10 times the cathedral's capacity—applied for tickets. In addition, Poznansky writes that on the day of the funeral, "[i]t seemed that all the inhabitants of St. Petersburg had come out on to the streets to pay their last respects. The whole of Nevsky Prospect was packed with people.

What those people saw as they lined the streets was equally great. Behind entire rows of wreaths marched the clergy, wearing white cassocks. Behind them was the coffin, on a hearse pulled by three pairs of horses. Tchaikovsky's family followed the hearse. After them, in order of importance, came the representatives of various institutions.

After a short liturgy the coffin was placed on a hearse to be taken to Kazan Cathedral, following a special route that took the procession past the Mariinsky Theatre. Grand Duke Konstantin and other members of the imperial family arrived at the cathedral in time for the main religious service, which lasted until 5 o'clock in the afternoon.

Particularly absent from Tchaikovsky's funeral was his former patroness, Nadezhda von Meck, though she sent a very expensive wreath. She was already gravely ill and moved with great difficulty. When Anna Davydova-von Meck was later asked how her mother-in-law had endured the news of the composer's death, Anna replied, "She did not endure it," adding that von Meck soon felt much worse. Madame von Meck died three months after Tchaikovsky, in Nice.

He was interred in Tikhvin Cemetery at the Alexander Nevsky Monastery. His grave is located near those of fellow-composers Alexander Borodin and Modest Mussorgsky.

A curious and, in retrospect, potentially ironic event concluded the day of the funeral - Tchaikovsky's brother Modest's comedy Prejudices premiered in Saint Petersburg. Tchaikovsky had delayed his return to his home in Klin in anticipation of this event. The premiere had been delayed due to the composer's death and was rescheduled for two days later, which turned out to be the day of the funeral. Modest decided against a second postponement, presumably feeling the need for some distraction. Reviews were negative, a reviewer from the St Petersburg Register writing, "On Thursday, the day of P.I. Tchaikovsky's burial, M.I. Tchaikovsky was buried at the Aleksandrinsky Theatre."

Musical works

Ballets

Tchaikovsky is well known for his ballets, although it was only in his last years, with his last two ballets, that his contemporaries came to really appreciate his finer qualities as ballet music composer.

- Swan Lake, Op. 20, (1875–1876): Tchaikovsky's first ballet, it was first performed (with some omissions) at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow in 1877. It was not until 1895, in a revival by Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov that the ballet was presented in the definitive version it is still danced in today (the music for this revival was much revised by the composer Riccardo Drigo in a version still used by most ballet companies today).

- Sleeping Beauty, Op. 66, (1888–1889): This work Tchaikovsky considered to be one of his best. Commissioned by the director of the Imperial Theatres, Ivan Vsevolozhsky, its first performance was in January, 1890 at the Mariinsky Theatre in St Petersburg.

- The Nutcracker, Op. 71, (1891–1892): Tchaikovsky himself was less satisfied with this, his last ballet. Though he accepted the commission (again granted by Ivan Vsevolozhsky), he did not particularly want to write it (though he did write to a friend while composing the ballet: "I am daily becoming more and more attuned to my task.") This ballet premiered on a double-bill with his last opera, Iolanta. Among other things, the score of Nutcracker is noted for its use of the celesta, an instrument that the composer had already employed in his much lesser known symphonic poem The Voyevoda (premiered 1891).^ Although well-known in Nutcracker as the featured solo instrument in the "Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy" from Act II, it is employed elsewhere in the same act.

- Note: This was the only ballet from which Tchaikovsky himself derived a suite (the "suites" from the other ballets were devised by other hands). The Nutcracker Suite is often mistaken for the ballet itself, but it consists of only eight selections from the score, and intended for concert performance.

Operas

Tchaikovsky completed ten operas, although one of these is mostly lost and another exists in two significantly different versions. In the West his most famous are Eugene Onegin and The Queen of Spades.

-

- Full score destroyed by composer, but posthumously reconstructed from sketches and orchestral parts

- Undina (Ундина or Undine, 1869)

-

- Not completed. Only a march sequence from this opera saw the light of day, as the second movement of his Symphony #2 in C Minor and a few other segments are occasionally heard as concert pieces. Interestingly, while Tchaikovsky revised the Second symphony twice in his lifetime, he did not alter the second movement (taken from the Undina material) during either revision. The rest of the score of Undina was destroyed by the composer.

-

- Premiere April 24 [OS April 12], 1874, St Petersburg

- Vakula the Smith (Кузнец Вакула or Kuznets Vakula), Op. 14, 1874;

-

- Revised later as Cherevichki, premiere December 6 [OS November 24], 1876, St Petersburg

-

- Premiere March 29 [OS March 17] 1879 at the Moscow Conservatory

-

- Premiere February 25 [OS February 13], 1881, St Petersburg

- Cherevichki (Черевички; revision of Vakula the Smith) 1885

-

- Premiere November 1 [OS October 20] 1887, St Petersburg

- The Queen of Spades (Пиковая дама or Pikovaya dama), Op. 68, 1890

-

- Premiere December 19 [OS December 7] 1890, St Petersburg

- Iolanta (Иоланта or Iolanthe), Op. 69, 1891

-

- First performance: Maryinsky Theatre, St Petersburg, 1892. Originally performed on a double-bill with The Nutcracker

(Note: A "Chorus of Insects" was composed for the projected opera Mandragora [Мандрагора] of 1870).

Symphonies

Tchaikovsky's earlier symphonies are generally optimistic works of nationalistic character, while the later symphonies are more intensely dramatic, particularly the Sixth, generally interpreted as a declaration of despair. The last three of his numbered symphonies (the fourth, fifth and sixth) are recognized as highly original examples of symphonic form and are frequently performed.

- No. 1 in G minor, Op. 13, Winter Daydreams (1866)

- No. 2 in C minor, Op. 17, Little Russian (1872)

- No. 3 in D major, Op. 29, Polish (1875)

- No. 4 in F minor, Op. 36 (1877–1878)

- Manfred Symphony, B minor, Op. 58; inspired by Byron's poem Manfred; Tchaikovsky labelled this work "a symphonic poem in four movements" (1885)

- No. 5 in E minor, Op. 64 (1888)

- No. 6 in B minor, Op. 74, Pathétique (1893)

- Symphony in E flat (unfinished). This work, abandoned by Tchaikovsky in 1892, was reused in part for the Third Piano Concerto and Andante and Finale for piano and orchestra. A reconstruction of the original symphony from the sketches and various reworkings was accomplished during 1951–1955 by the Soviet composer Semyon Bogatyrev, who brought the symphony into finished, fully orchestrated form and issued the score as Tchaikovsky's "Symphony No 7 in E-flat major."

Orchestral suites

Tchaikovsky also wrote four orchestral suites in the ten years between the 4th and 5th symphonies. He originally intended to designate one or more of these as a "symphony" but was persuaded to alter the title. The four suites are nonetheless symphonic in character, and, compared to the last three symphonies, are undeservedly neglected.

- Suite No. 1 in D minor, Op. 43 (1878-1879)

- Suite No. 2 in C major, Op. 53 (1883)

- Suite No. 3 in G major, Op. 55 (1884)

- Suite No. 4 in G major, "Mozartiana", Op. 61 (1887). This consists of four orchestrations of piano pieces by (or in one case, based on) Mozart:

-

- Little Gigue in G, K.574

- Minuet in D, K.355

- the Franz Liszt piano transcription of the chorus Ave verum corpus, K.618. (In 1862 Liszt wrote a piano transcription combining Gregorio Allegri's Miserere and Mozart's Ave verum corpus, published as "À la Chapelle Sixtine" (S.461). Tchaikovsky orchestrated only the part of this work that had been based on Mozart.)

- Variations on a theme of Gluck, K.455. (The theme was the aria "Unser dummer Pöbel meint", from his opera " La Rencontre imprévue, or Les Pèlerins de la Mecque").

In addition to the above suites, Tchaikovsky made a short sketch for a Suite in 1889 or 1890, which was not subsequently developed.

Tchaikovsky himself arranged the suite from the ballet The Nutcracker. He also considered making suites from his two other ballets, Swan Lake and The Sleeping Beauty. He ended up not doing so, but after his death, others compiled and published suites from these ballets.

Concerti and concert pieces

- Piano Concerto No. 1 in B-flat minor, Op. 23(1874–1875): Of his three piano concerti, it is best known and most highly regarded, and one of the most popular piano concertos ever written. It was initially rejected by its dedicatee, the pianist Nikolai Rubinstein, as poorly composed and unplayable, and subsequently premiered by Hans von Bülow (who was delighted to find such a piece to play) in Boston, Massachusetts on 25 October 1875. Rubinstein later admitted his error of judgement, and included the work in his own repertoire.

- Serenade Melancolique, Op.26, for Violin and Orchestra

- Variations on a Rococo theme Op.33 for violoncello and orchestra, (1876), The piece was written between December 1876 and March 1877, for and with the help of the German cellist Wilhelm Fitzenhagen (a professor at the Moscow Conservatory). The dedicatee revised and reordered it somewhat in 1878, but the composer allowed the changes to stand. It was well received at its first performances and Fitzenhagen himself took the piece with him on a tour of Europe. Though not really a concerto, it was the closest Tchaikovsky ever came to writing a full concerto for cello.

- Valse-Scherzo, Op.34, for Violin and Orchestra

- Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 35, (1878), was composed in less than a month during March and April 1878, but its first performance was delayed until 1881 because Leopold Auer, the violinist to whom Tchaikovsky had intended to dedicate the work, refused to perform it: he stated that it was unplayable. Instead it was first performed by the relatively unknown Austrian violinist Adolf Brodsky, who received the work by chance. This violin concerto is one of the most popular concertos for the instrument and is frequently performed today.

- Piano Concerto No. 2, Op. 44, (1879), is an eloquent, less extroverted piece with a violin and cello added as soloists in the second movement.

- Concert Fantasia in G, Op.56, for piano and orchestra

- Pezzo capriccioso, Op.62, (1888), for Cello and Orchestra

- Piano Concerto No. 3, Op. 75 posth. (1892): Commenced after the Symphony No. 5, what became the Third Piano Concerto and Andante and Finale for piano and orchestra was intended initially to be the composer's next (i.e., sixth) symphony.

- Andante and Finale, Op. 79 posth. (1895): After Tchaikovsky's death, the composer Sergei Taneyev completed and orchestrated the Andante and Finale from Tchaikovsky's piano arrangement of these two movements, publishing them as Op. 79.

- Concertstuck. for Flute and Strings, TH 247 op. posth. (1893): the piece, after having been lost for 106 years, was found and reconstructed by James Strauss in 1999 in S. Petersburg.

- Cello Concerto (1893): Completed by Yuriy Leonovich and Brett Langston in 2006.

Other works

For orchestra

- Romeo and Juliet Fantasy Overture, (1869 revised 1870, 1880). This piece contains one of the world's most famous melodies. The "love theme" has been used countless times in commercials and movies, frequently as a spoof to traditional love scenes.

- Festival Overture on the Danish national anthem, Op. 15, (1866).

- The Tempest, Symphonic Fantasia after Shakespeare, Op. 18, (1873)

- Slavonic March/Marche Slave, Op. 31, (1876). This piece is another well-known Tchaikovsky piece and is often played in conjunction with the 1812 Overture. This work uses the Tsarist National Anthem. It is mostly in a minor key and is yet another very recognisable piece, commonly referenced in cartoons, commercials and the media. The piece is much in the style of a capriccio.

- Francesca da Rimini, Op. 32, (1876). This piece has been described as "pure melodrama" similar to stretches of Verdi operas; some passages are similar to sword-fight clashes in Romeo and Juliet.

- Capriccio Italien, Op. 45, (1880). This piece is a traditional caprice or capriccio (in Italian) in an Italian style. Tchaikovsky stayed in Italy in the late 1870s to early 1880s and throughout the various festivals he heard many themes, some of which were played by trumpets, samples of which can be heard in this caprice. It has a lighter character than many of his works, even "bouncy" in places, and is often performed today in addition to the 1812 Overture. The title used in English-speaking countries is a linguistic hybrid: it contains an Italian word ("Capriccio") and a French word ("Italien"). A fully Italian version would be Capriccio Italiano; a fully French version would be Caprice Italien.

- Serenade in C for String Orchestra, Op. 48, (1880). The first movement, In the form of a sonatina, was an homage to Mozart. The second movement is a Waltz, followed by an Elegy and a spirited Russian finale, Tema Russo. In his score, Tchaikovsky supposedly wrote, "The larger the string orchestra, the better will the composer's desires be fulfilled."

- 1812 Overture, Op. 49, (1880). This piece was reluctantly written by Tchaikovsky to commemorate the Russian victory over Napoleon in the Napoleonic Wars. It is known for its traditional Russian themes (such as the old Tsarist National Anthem) as well as its famously triumphant and bombastic coda at the end which uses 16 cannon shots and a chorus of church bells. Despite its popularity, Tchaikovsky wrote that he "did not have his heart in it".

- Coronation March, Op. 50, (1883). The mayor of Moscow commissioned this piece for performance in May 1883 at the coronation of Tsar Alexander III. Tchaikovsky's arrangement for solo piano and E. L. Langer's arrangement for piano duet were published in the same year.

- Concert Overture The Storm, Op. 76, ( 1860).

- Fate, Op. 77, (1868).

- The Voyevoda, Op. 78, (1891).

For voices and orchestra

- The Snow Maiden (1873), incidental music for Alexander Ostrovsky's play of the same name. Ostrovsky adapted and dramatized a popular Russian fairy tale, and the score that Tchaikovsky wrote for it was always one of his own favorite works. It contains much vocal music, but it is not a cantata, nor an opera.

- Hamlet (1891), incidental music for Shakespeare's play. The score uses music borrowed from Tchaikovsky's overture of the same name, as well as from his Symphony No. 3, and from The Snow Maiden, in addition to original music that he wrote specifically for a stage production of Hamlet. The two vocal selections are a song that Ophelia sings in the throes of her madness, and a song for the First Gravedigger to sing as he goes about his work.

Solo and chamber music

- String Quartet in B-Flat Major, Op.Posth. (1865)

- String Quartet No. 1 in D major, Op. 11 (1871)

- String Quartet No. 2 in F major, Op. 22 (1874)

- String Quartet No. 3 in E-Flat minor, Op. 30 (1875)

- The Seasons, Op. 37a (1876)

- Piano Sonata in G Major, Op.37 (1878)

- Souvenir d'un lieu cher for violin and piano, Op. 42 (Meditation, Scherzo and Melody) (1878)

- Russian Vesper Service, Op. 52 (1881)

- Piano Trio in A minor, Op. 50 (1882)

- Dumka, Russian rustic scene in C minor for piano, Op. 59 (1886)

- String Sextet Souvenir de Florence, Op. 70 (1890)

- 18 Piano Pieces, Op.72 (1892). This also exists in a Cello Concerto arrangement by Gaspar Cassadó.

For a complete list of works by opus number, see . For more detail on dates of composition, see .

Citations

- ^ Note: His names are also transliterated Piotr, Petr, or Peter; Ilitsch, Ilich, Il'ich or Illyich; and Tschaikowski, Tschaikowsky, Chajkovskij and Chaikovsky (as well as many other versions)

- ^ Letter to Anatoly Tchaikovsky, February 25, 1878, as quoted in Holden, Anthony, Tchaikovsky: A Biography (New York: Random House, 1995), 172

- ^ See Holden, 375-386

- ^ See, e.g., Tchaikovsky's Last Days by Alexander Poznansky.

- ^ Holden, 390

- ^ Holden, 391

- ^ Holden, 399

- ^ Holden, 399

- ^ The Daily Telegraph: " http://www.telegraph.co.uk/arts/main.jhtml;jsessionid=AAHCFNMHZ13QZQFIQMGSFFWAVCBQWIV0?xml=/arts/2007/01/15/bmbbc15.xml&page=2 "How did Tchaikovsky die?" Retrieved March 25, 2007.

- ^ Poznansky, Tchaikovsky: The Quest for the Inner Man, 594

- ^ Poznansky, Tchaikovsky: The Quest for the Inner Man, 594

- ^ Poznansky, Tchaikovsky: The Quest for the Inner Man, 595

- ^ Poznansky, Tchaikovsky: The Quest for the Inner Man, 594-595

- ^ Poznansky, Tchaikovsky: The Quest for the Inner Man, 611

- ^ Poznansky, Tchaikovsky: The Quest for the Inner Man, 595-596

- ^ Wiley, Roland. 'Tchaikovsky, Pyotr Il′yich, §6(ii): Years of valediction, 1889–93: The last symphony'; Works: solo instrument and orchestra; Works: orchestral, Grove Music Online (Accessed 07 February 2006), < http://www.grovemusic.com> (subscription required). Brown, David. Tchaikovsky: the Final Years (1885-1893). New York: W.W. Norton, 1991, pp. 388-391, 497.

- ^