Abugida

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Linguistics

| This article contains Indic text. Without rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes or other symbols instead of Indic characters; or irregular vowel positioning and a lack of conjuncts. |

An abugida (pronounced /ˌɑːbuːˈɡiːdə/, from Ge‘ez አቡጊዳ ’äbugida or Amharic አቡጊዳ ’abugida) is a segmental writing system which is based on consonants but in which vowel notation is obligatory. About half the writing systems in the world are abugidas, including the extensive Brahmic family of scripts used in South and Southeast Asia.

In general, a full letter of an abugida transcribes a consonant. Full letters are written in a linear sequence in a consistent direction. Vowels are dependent on the consonant. They are written through modification of the consonant letter, either by means of diacritics which are placed in a vowel-dependent position relative to the consonant (rather than always progressing in the same direction as the sequence of full letters) or through changes in the form of the consonant itself.

Vowels not preceded by a consonant may be represented with:

- a zero consonant letter with dependent vowel signs attached

- separate full letters for each initial vowel, that are distinct from the dependent vowel signs

Consonants not followed by a vowel may be represented with:

- a dependent vowel sign which explicitly indicates lack of a vowel ( virama)

- lack of a dependent vowel sign (often with ambiguity between no vowel and a default inherent vowel)

- a dependent vowel sign for a short or neutral vowel such as schwa (with ambiguity between no vowel and that short or neutral vowel)

- conjunct consonant letters where two or more consonant letters are graphically joined in a ligature

- dependent consonant signs, which may be smaller and/or differently placed versions of the full consonant letters, or distinct signs

The term abugida was adopted into English as a linguistic term by Peter T. Daniels. It is the colloquial name of the Ge‘ez script, derived from the first four letters aləf, bet, gäməl, dənt (in the biblical A B G D order of Hebrew) graded by the first four vowel forms, much as the term abecedary is derived from the Latin a be ce de. As Daniels used the word, an abugida contrasts with a syllabary, where letters with shared consonants or vowels show no particular resemblance to each another, and with an alphabet proper, where independent letters are used to denote both consonants and vowels. Traditionally, abugidas have been considered to be syllabaries or intermediate between syllabaries and alphabets ("semi-syllabaries", "alpha-syllabaries", etc.). Less formally, however, abugidas are simply called "alphabets".

Writing systems |

|---|

| History Grapheme List of writing systems |

| Types |

| Alphabet Featural alphabet Abjad Abugida Syllabary Logography |

| Related topics |

| Pictogram Ideogram |

Description

There are three principal families of abugidas, which function somewhat differently.

- The largest and the oldest is the Brahmic family of India and Southeast Asia, in which vowels are marked with diacritics and syllable-final consonants, when they occur, are indicated with ligatures, diacritics, or with a special vowel-canceling mark.

- In the Ethiopic family, vowels are marked by modifying the shapes of the consonants, and one of these pulls double duty for final consonants.

- In the Cree family, vowels are marked by rotating or flipping the consonants, and final consonants are indicated with either special diacritics or superscript forms of the main initial consonants.

Thaana of the Maldives has dependent vowels and a zero vowel sign, but no inherent vowel.

| Feature | North Indic | South Indic | Ethiopic | Canadian | Thaana |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vowel after consonant | Dependent sign (diacritic) |

Change shape (fused diacritic) |

Rotation or reflection | Dependent sign (diacritic) |

|

| Initial vowel letter(s) | Full letters | Zero consonant | Glottal stop | Zero consonant | |

| Absence of vowel sign | [ə], [ɔ], [a], or [o] | [ə] | Vowel indication obligatory | ||

| Virama (zero vowel sign) | Often | Consistently | None | Always | |

| Consonant ligatures | Often | Few or none | None | ||

| Final consonant dependents | Usually ṃ, ḥ only | No | Yes (all) | No | |

| Distinct final forms | ṃ, ḥ only | N/A | Western only | N/A | |

| Final consonant position | Top or inline | Inline | N/A | Inline, small, raised | N/A |

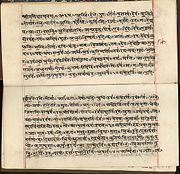

Indic (Brahmic)

Indic scripts originated in South Asia and spread to Southeast Asia. All surviving Indic scripts are descendants of the Brahmi alphabet. Today they are used in most languages of South Asia (except Urdu and other languages of Pakistan) and mainland Southeast Asia (Burma, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia; but not Malaysia or Vietnam). The primary division is into North Indic scripts used in North India, Nepal, Tibet, Bhutan and South Indic scripts used in South India, Sri Lanka, and Southeast Asia. South Indic letter forms are very rounded; North Indic less so, though Oriya, Golmol and Litumol of Nepal script are rounded. Most North Indic scripts' full letters incorporate a horizontal line at the top, with Gujarati script an exception; South Indic scripts do not.

Indic scripts indicate vowels through dependent vowel signs (diacritics) around the consonants, often including a sign that explicitly indicates the lack of a vowel. If a consonant has no vowel sign, this indicates a default vowel. Vowel diacritics may appear above, below, to the left, to the right, or around the consonant.

The most populous Indic script is Devanagari, used for Hindi, Bhojpuri, Marathi, Nepali, and often Sanskrit. A basic letter such as क represents a syllable with the default vowel, in this case ka ([kə]), or, in final position, a final consonant, in this case k. This inherent vowel may be changed by adding vowel marks ( diacritics), producing syllables such as कि ki, कु ku, के ke, को ko. The mora a consonant letter represents, either with or without a marked vowel, is called an akshara.

| position | syllable | pronunciation | base form | script |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| above | के | /keː/ | क /k(a)/ | Devanagari |

| below | कु | /ku/ | ||

| left | कि | /ki/ | ||

| right | को | /kοː/ | ||

| around | கௌ | /kau/ | க /ka/ | Tamil |

| within | ಕಿ | /ki/ | ಕ /ka/ | Kannada |

In many of the Brahmic scripts, a syllable beginning with a cluster is treated as a single character for purposes of vowel marking, so a vowel marker like ि -i, falling before the character it modifies, may appear several positions before the place where it is pronounced. For example, the game cricket in Hindi is क्रिकेट krikeţ; the diacritic for /i/ appears before the consonant cluster /kr/, not before the /r/. A more unusual example is seen in the Batak alphabet: Here the syllable bim is written ba-ma-i-(virama). That is, the vowel diacritic and virama are both written after the consonants for the whole syllable.

In many abugidas, there is also a diacritic to suppress the inherent vowel, yielding the bare consonant. In Devanagari, क् is k, and ल् is l. This is called the virama in Sanskrit, or halant in Hindi. It may be used to form consonant clusters, or to indicate that a consonant occurs at the end of a word. For text information processing on computer, other means of expressing these functions include special conjunct forms in which two or more consonant characters are merged to express a cluster, such as Devanagari: क्ल kla. (Note that on some fonts display this as क् followed by ल, rather than forming a conjunct. This expedient is used by ISCII and South Asian scripts of Unicode.) Thus a closed syllable such as kal requires two akshara to write.

The Róng script used for the Lepcha language goes further than other Indic abugidas, in that a single akshara can represent a closed syllable: Not only the vowel, but any final consonant is indicated by a diacritic. For example, the syllable [sok] would be written as something like s̥̽, here with an underring representing /o/ and an overcross representing the diacritic for final /k/. Most other Indic abugidas can only indicate a very limited set of final consonants with diacritics, such as /ŋ/ or /r/, if they can indicate any at all.

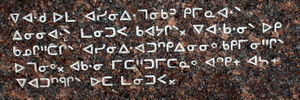

Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics

In the family known as Canadian Aboriginal syllabics, vowels are indicated by changing the orientation of the akshara. Each vowel has a consistent orientation; for example, Inuktitut ᐱ pi, ᐳ pu, ᐸ pa; ᑎ ti, ᑐ tu, ᑕ ta. Although there is a vowel inherent in each, all rotations have equal status and none can be identified as basic. Bare consonants are indicated either by separate diacritics, or by superscript versions of the aksharas; there is no vowel-killer mark.

Ethiopic

In Ethiopic, which gave us the word abugida, the diacritics have fused to the consonants to the point that they must be considered modifications of the form of the letters. Children learn each modification separately, as in a syllabary; nonetheless, the graphic similarities between syllables with the same consonant is readily apparent, unlike the case in a true syllabary.

Though now an abugida, the Ge'ez alphabet was actually an abjad until the 4th century AD. In the Ge'ez abugida, the form of the letter itself may be altered. For example, ሀ hä [hə] (base form), ሁ hu (with a right-side diacritic that does not alter the letter), ሂ hi (with a subdiacritic that compresses the letter, so that the whole fidel occupies the same amount of space), ህ hə [hɨ] or [h] (where the letter is modified with a kink in the left arm).

Borderline cases

Voweled abjads

Consonantal scripts (" abjads") are normally written without indication of many vowels. However in some contexts like teaching materials or scriptures, Arabic and Hebrew are written with full indication of vowels via diacritic marks ( harakat, niqqud) making them effectively abugidas. The Brahmic and Ethiopic families are thought to have originated from the Semitic abjads by the addition of vowel marks.

The Arabic-alphabet scripts used for Kurdish in Iraq and for Uighur in Xinjiang, China are fully voweled, but since the vowels are full letters rather than diacritics, and there are no inherent vowels, these are considered alphabets rather than abugidas.

Phagspa

The imperial Mongol script called Phagspa was derived from the Tibetan abugida, but all vowels are written in-line rather than as diacritics. However, it retains the features of having an inherent vowel /a/ and having distinct initial vowel letters.

Pahawh

Pahawh Hmong is a non-segmental script that indicates syllable onsets and rimes, such as consonant clusters and vowels with final consonants. Thus it is not segmental and cannot be considered an abugida. However, it superficially resembles an abugida with the roles of consonant and vowel reversed. Most syllables are written with two letters in the order rime–onset (typically vowel-consonant), even though they are pronounced as onset-rime (consonant-vowel), rather like the position of the /o/ vowel in the Indic abugidas, which is written before the consonant. Pahawh is also unusual in that, while an inherent rime /āu/ (with mid tone) is unwritten, it also has an inherent onset /k/. For the syllable /kau/, which requires one or the other of the inherent sounds to be overt, it is /au/ that is written. Thus it is the rime (vowel) which is basic to the system.

Meroitic

It is difficult to draw a dividing line between abugidas and other segmental scripts. For example, the Meroitic script of ancient Sudan did not indicate an inherent a (one symbol stood for both m and ma, for example), and is thus similar to Brahmic family abugidas. However, the other vowels were indicated with full letters, not diacritics or modification, so the system was essentially an alphabet that did not bother to write the most common vowel.

Shorthand

Several systems of shorthand use diacritics for vowels, but they do not have an inherent vowel, and are thus more similar to Thaana and Kurdish than to the Brahmic scripts. The Gabelsberger shorthand system and its derivatives modify the following consonant to represent vowels. The Pollard script, which was based on shorthand, also uses diacritics for vowels; the placements of the vowel relative to the consonant indicates tone.

Evolution

As the term alphasyllabary suggests, abugidas have been considered an intermediate step between alphabets and syllabaries. Historically, abugidas appear to have evolved from abjads (vowelless alphabets). They contrast with syllabaries, where there is a distinct symbol for each syllable or consonant-vowel combination, and where these have no systematic similarity to each other, and typically develop directly from logographic scripts. Compare the Devanagari examples above to sets of syllables in the Japanese hiragana syllabary: か ka, き ki, く ku, け ke, こ ko have nothing in common to indicate k; while ら ra, り ri, る ru, れ re, ろ ro have neither anything in common for r, nor anything to indicate that they have the same vowels as the k set.

Most Indian and Indochinese abugidas appear to have first evolved from abjads with the Kharoṣṭhī and Brāhmī scripts; the abjad in question is usually considered to be the Aramaic one, but while the link between Aramaic and Kharosthi is more or less undisputed, this is not the case with Brahmi. The Kharosthi family does not survive today, but Brahmi's descendants include most of the modern scripts of South and Southeast Asia. Although Ge'ez derived from a different abjad, one theory is that its evolution into an abugida may have been influenced by Christian missionaries from India.

Other types of writing systems

- Abjad

- Alphabet

- Logogram

- Syllabary

Partial list of abugidas

True abugidas

- Brahmic family, descended from Brāhmī (c. 6th century BC)

- Ahom

- Balinese

- Balti

- Batak

- Baybayin, pre-colonial script of Tagalog and other Philippine languages

- Bengali

- Bhujimol script

- Box-head a script in India

- Bugis also known as Makassar or Lontara

- Buhid, used by Mangyans in Mindoro, Philippines

- Burmese

- Chalukya

- Cham

- Chola

- Devanagari (used to write Nepali, Sanskrit, Pali, modern Hindi, Marathi etc.)

- Dehong Dai

- Golmol script

- Grantha

- Gujarati

- Gurmukhi script

- Hanuno'o, a script used by Mangyans in Mindoro, Philippines

- Javanese script

- Kadamba

- Kaithi

- Kannada

- Khmer

- Lanna

- Lepcha

- Limbu

- Lao (before spelling reforms)

- Malayalam

- Manipuri

- Modi used to write Marathi

- Oriya

- Old Kawi progenitor of Indonesian and Philippine scripts

- Pachumol script

- Phags-Pa created for Kublai Khan's Yuan China

- Prachalit Nepal script

- Ranjana

- Redjang

- Sharada

- Siddham used to write Sanskrit

- Sinhala

- Sorang Sompeng

- Sourashtra

- Soyombo

- Syloti Nagri

- Tagbanwa in Palawan, Philippines

- Tai Dam

- Tamil

- Telugu

- Thai

- Tibetan

- Tirhuta used to write Maithili

- Tocharian - extinct

- Varang Kshiti

- Vatteluttu aka round script

- Kharoṣṭhī (extinct), from the 3rd century BC

- Ge'ez (Ethiopic), from the 4th century AD

- Canadian Aboriginal syllabics

- Cree- Ojibwe syllabics

- Inuktitut syllabics

- Blackfoot syllabics

- Carrier syllabics

Abugida-like scripts

- Meroitic (extinct)

- Thaana

- Pitman shorthand

- Pollard script