George I of Great Britain

2008/9 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: British History 1500-1750; Monarchs of Great Britain

| George I | |

|---|---|

| King of Great Britain and Ireland; Elector of Hanover; Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg (more...) | |

|

|

| Portrait by Sir Godfrey Kneller | |

| Reign | 1 August 1714 – 11 June 1727 |

| Coronation | 20 October 1714 |

| Predecessor | Anne |

| Successor | George II |

| Consort | Sophia Dorothea of Celle ( 1682 - 1694) |

| Issue | |

| George II Sophia, Queen in Prussia |

|

| Full name | |

| George Louis German: Georg Ludwig |

|

|

Detail Titles and styles |

|

| HM The King HRH The Elector of Hanover HSH The Hereditary Prince of Hanover HSH The Hereditary Prince of Brunswick-Lüneburg HSH Duke Georg Ludwig of Brunswick-Lüneburg |

|

| Royal house | House of Hanover |

| Father | Ernest Augustus, Elector of Hanover and Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg |

| Mother | Sophia, Countess Palatine of Simmern |

| Born | 28 May 1660 Leine Castle, Hanover |

| Died | Template:Euro death date and age Osnabrück, Hanover |

| Burial | 4 August 1727 Herrenhausen Palace, Hanover |

George I (George Louis; 28 May 1660 – 11 June 1727) was the first Hanoverian King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, from 1 August 1714 until his death. He was also the Archbannerbearer (afterwards Archtreasurer) and a Prince Elector of the Holy Roman Empire.

Early life

George was born on 28 May 1660 in Hanover, Germany. He was the eldest son of Ernest Augustus, Elector of Hanover and Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg, a German prince, and of his wife, Sophia. His grandmother was the sister of Charles I of England and his great-grandfather was James I of England. Duke George of Brunswick-Lüneburg, as he was then known, was the heir-apparent to his father's German territory.

In 1682, George married his first cousin, the Princess Sophia of Celle, who was the only child of his father's elder brother. They had two children, George (b. 1683) and Sophia Dorothea (b. 1687). The couple were however soon estranged; George preferred the society of his mistress, Ehrengard Melusine von der Schulenburg, whom he later created Duchess of Munster and Kendal in Great Britain, and by whom he had at least three illegitimate children.

Sophia, meanwhile, had her own romantic connection with the Swedish Count Philip Christoph von Königsmarck. Threatened with the scandal of an elopement, the Hanoverian court ordered the lovers to desist, and George appears to have countenanced a plan to murder Königsmarck. The count was killed in July 1694, and his body was then thrown into a river. The murder appears to have been committed by four of George's courtiers, one of whom is said to have been paid the enormous sum of 150,000 thalers, which in that day was about one hundred times the annual salary of the highest-paid minister.

George's marriage to Sophia was dissolved, not on the grounds that either of them committed adultery, but on the grounds that Sophia had "abandoned" her husband. With the concurrence of her father, George had Sophia imprisoned in the Castle of Ahlden in her native Celle. She was denied access to her children and her father, and forbidden to remarry. She was however endowed with an income, establishment and servants, and was allowed to ride in a carriage outside her castle, albeit under supervision.

Early reign

In 1698, Ernst August died, leaving all of his territories to George, with the exception of the Prince-Bishopric of Osnabrück. (The Prince-Bishopric was not an hereditary title; instead, it alternated between Protestant and Roman Catholic incumbents.) George thus, on 23 January 1698, became Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg (also known as Hannover, after its capital), and thereby the Archbannerbearer (a prestigious sinecure) and, most importantly, a Prince-Elector of the Holy Roman Empire. His court in Hanover was graced by many cultural icons, such as the mathematician Gottfried Leibniz and the composer Händel.

Shortly after George's accession to his paternal dukedom, the Parliament of England passed the Act of Settlement 1701, whereunder George's mother, the Electress Sophia, was designated heir to the British Throne if the then-reigning monarch (William III) and his sister-in-law Princess Anne of Denmark (the later Queen Anne) both died without issue. The succession was so designed because Sophia was the closest Protestant relative of the British Royal Family; numerous Catholics with superior hereditary claims were bypassed. In England, the Tories generally opposed allowing a foreigner to succeed to the Throne, whilst the Whigs favoured a Protestant successor regardless of nationality. George is said to have been reluctant to accept the English plan, but his Hanoverian advisors suggested that he should acquiesce so that his German possessions would become more secure.

| British Royalty |

|---|

| House of Hanover |

|

| George I |

| George II |

| Sophia, Queen in Prussia |

Shortly after George's accession in Hanover, the War of the Spanish Succession broke out. At issue was the right of Philip, the grandson of the French King Louis XIV, to succeed to the Spanish Throne under the terms of the will of the Spanish King Charles II. The Holy Roman Empire, the United Provinces, England, Hanover and many other German states opposed Philip's right to succeed because they feared that France would become too powerful if it also could control Spain.

George's support for England may have conciliated many Englishmen, but it did not impress the people of Scotland. The English Parliament had settled on Sophia, Electress of Hanover, without consulting the Estates of Scotland (the Scottish Parliament). In 1703, the Estates passed a bill that declared that they would elect Queen Anne's successor from amongst the Protestant descendants of past Scottish monarchs. This successor would not be the same individual as the successor to the English Throne, unless numerous political and economic concessions were made by England. The Royal Assent was originally withheld, which caused the Scottish Estates to refuse to raise taxes and threaten to withdraw troops from the army fighting in the War of the Spanish Succession. In 1704, Anne capitulated, and her Assent was granted to the bill, which became the Act of Security 1704. Angered, the English Parliament passed several measures which restricted Anglo-Scottish trade and crippled the Scottish economy. In 1707, the Act of Union was passed; it united England and Scotland into a single political entity, the Kingdom of Great Britain. The rules of succession established by the Act of Settlement were retained. The House of Hanover was not entirely acceptable to many Scotsmen, as would be later reflected by rebellions during George I's reign.

In 1706, the Elector of Bavaria was deprived of his offices and titles for siding with France against the Empire. In 1708, the Reichstag, or Imperial Diet, formally confirmed George's position as a Prince-Elector and in 1710 conferred upon him the dignity of Archtreasurer of the Empire, formerly held by the Elector Palatine - the absence of the Elector of Bavaria allowed a re-shuffling of offices. The War of the Spanish Succession would continue until 1713, when it ended indecisively with the ratification of the Treaty of Utrecht. Philip was allowed to succeed to the Spanish Throne, but he was removed from the line of succession to the French Throne.

Accession in Great Britain

George's mother, the Electress Sophia, died only a few weeks before Anne, Queen of Great Britain. Although there were fifty-two possible heirs to the throne of Great Britain at the time and the fact that direct lines were considered to be direct through males and not women, pursuant to the Act of Union 1707, George became King of Great Britain, when Anne died on 1 August 1714. George strongly agreed with the ideas of the Whigs at the time.

He did not arrive in Great Britain until 18 September; during his absence, the Lord Chief Justice of the King's Bench acted as a regent. George was crowned at Westminster Abbey on 20 October.

Upon his accession the practice relating to the dignity of princes was changed. Before the Hanoverians, the only princely dignities were those of Prince of Wales (customarily granted to the heir-apparent) and Princess Royal (customarily granted to the Sovereign's eldest daughter). The other members of the Royal Family were only entitled to the styles "Lord" and "Lady". George I, however, was accustomed to the German practice, whereunder the princely dignity was more common. Consequently, the Sovereign's children and grandchildren in the male line became Princes and Princesses styled "Royal Highness," and great-grandchildren in the male line became Princes and Princesses styled "Highness".

George I primarily resided in Great Britain, though he often visited his home in Hanover. During the King's absences, power was vested either in his son, George, Prince of Wales, or in a committee of "Guardians and Justices of the Kingdom". Even whilst he was in Great Britain, the King occupied himself with Hanoverian concerns. He spoke poor English; instead, he spoke his native German, or French. Since many believed that he was not fluent in English, George I was ridiculed by his British subjects, and many of his contemporaries thought him unintelligent. During his reign, the powers of the monarchy diminished and the modern system of government by a Cabinet underwent development. Towards the end of his reign, actual power was held by a de facto Prime Minister, Sir Robert Walpole.

In 1715, when not even a year had passed after George's accession, he was faced with a Jacobite Rebellion, which became known as "The Fifteen". The Jacobites sought to put Anne's Catholic half-brother, James Francis Edward Stuart (whom they called "James III", and who was known to his opponents as the "Pretender") on the Throne. The Pretender instigated rebellion in Scotland, where support for Jacobitism was stronger than in England. John Erskine, 22nd Earl of Mar, an embittered Scottish nobleman who had previously supported the "Glorious Revolution", led the rebels. The Fifteen, however, was a dismal failure; Lord Mar's battle plans were poor, and the Pretender had not arrived in Scotland in time. By the end of the year 1715, the rebellion had all but collapsed. Faced with impending defeat, Lord Mar and the Pretender fled to France in the next February. After the rebellion was defeated, although there were some executions and forfeitures, the government's response was generally mild.

| Monarchical Styles of King George I of Great Britain |

|

|

|

| Reference style | His Majesty |

|---|---|

| Spoken style | Your Majesty |

| Alternative style | Sire |

Several members of the Tory Party sympathised with the Jacobites. George I began to distrust the Tories, and power thus passed to the Whigs. Whig dominance would be so great under George I that the Tories would not return to power for another half-century. As soon as the Whigs came to power, Parliament passed the Septennial Act 1715, which extended the maximum duration of Parliament to seven years (although it could be dissolved earlier by the Sovereign). Thus, Whigs already in power could remain in such a position for a greater period of time.

War and rebellion

After his accession in Great Britain, George's relationship with his son (which had always been poor) worsened. George, Prince of Wales constantly encouraged opposition to his father's policies. His home, Leicester House, became a meeting place for the King's political opponents. In 1717, the birth of a grandson led George I to quarrel with the Prince of Wales. The Prince and Princess of Wales, as well as their children, were all thrown out of the royal residence. George I and his son would later be reconciled, but would never again be on cordial terms.

George I was active in directing British foreign policy during his early years. In 1717, he contributed to the creation of the Triple Alliance, an anti-Spanish league composed of Great Britain, France and the United Provinces. In 1718, the Holy Roman Empire was added to the body, which became known as the Quadruple Alliance. The subsequent War of the Quadruple Alliance involved the same issue as the War of the Spanish Succession. The Treaty of Utrecht had allowed the grandson of Louis XIV of France, Philip, to succeed to the Spanish Throne, on the condition that he gave up his rights to succeed to the French Throne. Upon the death of Louis XIV, however, Philip attempted to violate the treaty and take the Crown of France. But with even the French fighting against him in the War, Philip's armies fared poorly. As a result, the Spanish and French Thrones remained separate.

George I was faced with a second rebellion in 1719. The Jacobites managed to secure the support of Spain, but stormy seas allowed only about three hundred Spanish troops to arrive in Scotland. A base was established at Eilean Donan Castle on the west Scottish coast, only for it to be destroyed by British ships a month later. Attempts to recruit Scottish soldiers yielded a fighting force of only about a thousand men. The Jacobites were poorly equipped, and were easily defeated by British artillery. The Scotsmen dispersed into the Highlands, and the Spaniards surrendered. The invasion of 1719 never posed any serious threat to the Government.

Ministries

In 1717, when the Whigs came to power, George's chief ministers included Sir Robert Walpole, Charles Townshend, 2nd Viscount Townshend, James Stanhope, 1st Viscount Stanhope (afterwards 1st Earl Stanhope) and Charles Spencer, 3rd Earl of Sunderland. In the same year, Lord Townshend and Walpole were removed from the Cabinet by their counterparts; Lord Stanhope became supreme in foreign affairs, and Lord Sunderland the same in domestic matters.

Lord Sunderland's power began to wane in 1719. He introduced a Peerage Bill, which attempted to limit the size of the House of Lords (mostly composed of Tory aristocrats), but was defeated. An even greater problem was the South Sea Bubble. In 1719, the South Sea Company proposed to convert £30,981,712 of the British national debt. At the time, government bonds were extremely difficult to trade due to unrealistic restrictions; for example, it was not permitted to redeem certain bonds unless the original debtor was still alive. Each bond represented a very large sum, and could not be divided and sold. Thus, the South Sea Company sought to convert high-interest, untradeable bonds to low-interest, easily-tradeable ones. The Company bribed Lord Stanhope to support their plan; they were also supported by Lord Sunderland. Company prices rose rapidly; the shares had cost £128 in January 1720, but were valued at £550 when Parliament accepted the scheme in May. The price reached £1000 by August. Uncontrolled selling, however, caused the stock to plummet to £150 by the end of September. Many individuals—including aristocrats—were completely ruined.

The economic crisis, known as the South Sea Bubble, made George I and his ministers extremely unpopular. Lord Stanhope died and Lord Sunderland resigned in 1721, allowing the rise of Sir Robert Walpole. (Lord Sunderland retained a degree of personal influence with George I until he died in 1722.) Walpole became George's primary minister, although the title " Prime Minister" was not formally applied to him; officially, he was only the First Lord of the Treasury. His management of the South Sea crisis helped avoid a dispute between the King and the House of Commons over responsibility for the affair.

Walpole strengthened his influence in the House of Commons through bribery. The Septennial Act, by lengthening the terms of members of the House from three to seven years, greatly aided Walpole's corrupt efforts. As requested by Walpole, George I created a new order of chivalry, The Most Honourable Order of the Bath. Walpole rewarded political supporters and bribed others by offering them membership of the prestigious organisation.

Walpole thus became extremely powerful; he, not the King, truly controlled the government. Walpole was allowed to choose and remove all ministers; George I merely rubber-stamped his decisions. George I did not even attend meetings of the Cabinet; all his communications were in private. George I only exercised substantial influence with respect to British foreign policy. He, with the aid of Lord Townshend, arranged for the ratification of the Treaty of Hanover, which was designed to protect British trade, by Great Britain, France and Prussia. Some of George I's successors—most notably his great-grandson, George III—attempted to reverse the shift in power, but proved unsuccessful.

Later years

George, although increasingly reliant on Sir Robert Walpole, could still have removed his ministers at will. Walpole was actually afraid of being removed towards the end of George I's reign, but such fears were put to an end when George I died in Osnabrück from a stroke on 11 June 1727. George was on his sixth trip to his native Hanover, where he was buried, in the chapel at Herrenhausen Palace.

George I's son succeeded him, becoming George II. George II, like his father, faced a Jacobite Rebellion. The Rebellion of 1745 ("the Forty-Five"), however, was better led than the Fifteen and Nineteen. The Jacobites were nonetheless defeated at the Battle of Culloden in 1746, effectively ending their resistance.

George II seriously contemplated removing Sir Robert Walpole from office, but was prevented from doing so by his wife. During George II's reign, the power of the Sovereign further deteriorated, and the power of the Prime Minister increased. George II's grandson and successor, George III, was often engaged in constitutional struggles with his ministers. By the reign of George III, however, the Prime Minister's power had grown so much that the King was often forced to appoint junior ministers against his will. After George III's reign, Sovereigns almost never exercised influence over the composition of the Cabinet. The decline of the power of the Sovereign, which had begun during George I's reign, was almost complete during the reign of the last Hanoverian monarch, Victoria.

Legacy

George I was extremely unpopular in Great Britain, especially due to his supposed inability to speak English; recent research, however, reveals that such an inability may not have existed later in his reign. His treatment of his wife, Sophia, was not well-received. The British perceived him as too German, and despised his succession of German mistresses. He earned the appellations "Geordie Whelps" and "German George".

Although unpopular, the Protestant George I was seen by most as a better alternative to the Roman Catholic Old Pretender. William Makepeace Thackeray indicates such ambivalent feelings when he writes, "His heart was in Hanover. He was more than 54 years of age when he came amongst us: we took him because we wanted him, because he served our turn; we laughed at his uncouth German ways, and sneered at him... I, for one, would have been on his side in those days. Cynical, and selfish, as he was, he was better than a King out of St Germains, the Old Pretender with a French King's orders in his pocket, and a swarm of Jesuits in his train."

Titles, styles, honours and arms

Titles

- 28 May 1660- 18 December 1679: His Serene Highness Duke Georg Ludwig of Brunswick-Lüneburg

- 18 December 1679- October 1692: His Serene Highness The Hereditary Prince of Brunswick-Lüneburg

- October 1692- 23 January 1698: His Serene Highness The Hereditary Prince of Hanover and Brunswick-Lüneburg

- 23 January 1698- 1 August 1714: His Royal Highness The Elector of Hanover, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg

- 1 August 1714– 11 June 1727: His Majesty The King

Styles

In Great Britain, George I used the official style "George, by the Grace of God, King of Great Britain, France and Ireland, Defender of the Faith, etc." In some cases (especially in treaties), the formula "Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg, Arch treasurer and Prince-Elector of the Holy Roman Empire" was added before the phrase "etc."

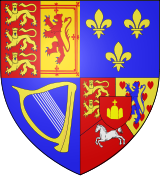

Arms

George I's arms were: Quarterly, I Gules three lions passant guardant in pale Or (for England) impaling Or a lion rampant within a tressure flory-counter-flory Gules (for Scotland); II Azure three fleurs-de-lys Or (for France); III Azure a harp Or stringed Argent (for Ireland); IV tierced per pale and per chevron (for Hanover), I Gules two lions passant guardant Or (for Brunswick), II Or a semy of hearts Gules a lion rampant Azure (for Lüneburg), III Gules a horse courant Argent (for Westfalen), overall an escutcheon Gules charged with the crown of Charlemagne Or (for the dignity of Arch treasurer of the Holy Roman Empire).

Ancestors

| George I of Great Britain | Father: Ernest Augustus, Elector of Hanover |

Father's father: George, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg |

Father's father's father: William, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg |

| Father's father's mother: Dorothea of Denmark |

|||

| Father's mother: Anne Eleonore of Hesse-Darmstadt |

Father's mother's father: Louis V, Landgrave of Hesse-Darmstadt |

||

| Father's mother's mother: Magdalena von Brandenburg |

|||

| Mother: Sophia of the Palatinate |

Mother's father: Frederick V, Elector Palatine |

Mother's father's father: Frederick IV, Elector Palatine |

|

| Mother's father's mother: Louise Juliana of Orange-Nassau |

|||

| Mother's mother: Elizabeth of Bohemia |

Mother's mother's father: James I of England |

||

| Mother's mother's mother: Anne of Denmark |

Issue

| Name | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| George II | 10 November 1683 | 25 October 1760 | married, 1705, Caroline of Ansbach; had issue |

| Sophia, Queen in Prussia | 26 March 1687 | 28 June 1757 | married, 1706, Frederick William, Margrave of Brandenburg (later Frederick William I of Prussia); had issue |